Section 1: Ancient Civilizations in Britain

This section begins with the origins of Britain’s history, reaching back to the Stone Age. It explores the earliest inhabitants and then moves through the many civilizations that shaped ancient Britain, including the Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, and Normans. Each group left a lasting imprint on British culture, society, and language.

Section 2: The Medieval Era and the Rise of New Orders

The medieval period brought monumental changes, including the devastation of the Black Death, which significantly reduced the population and led to the emergence of new social structures. This era also witnessed the beginnings of parliamentary systems in both England and Scotland, as well as key legal reforms. The growth of the English language also took shape during this time. This section concludes with the English Civil War, which paved the way for the Tudor dynasty.

Section 3: The Tudors, Stuarts, and the Elizabethan Golden Age

From Henry VIII’s reign in the early 1500s to the Glorious Revolution at the end of the 17th century, this section charts the significant reigns of the Tudor and Stuart monarchs. It highlights major historical milestones like the Spanish Armada’s defeat, early British colonization, and the cultural flowering of the Elizabethan era, which included great literary achievements by figures like William Shakespeare.

Section 4: From Monarchy to Modernity

This part explains how the constitutional monarchy developed, including the Act of Union that unified Scotland with England and Wales, creating the Kingdom of Great Britain. It discusses the Scottish clan uprisings, the Enlightenment of the 18th century, and the transformative Industrial Revolution, powered by steam and machinery. The rise and fall of the slave trade, culminating in its abolition, the formation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and Britain’s growing global empire are also detailed here, alongside democratic evolution.

Section 5: Britain in the World Wars

This section covers the dramatic impact of World War I and World War II on Britain, examining how the conflicts reshaped British society, economy, and international standing.

Section 6: Post-War Transformation and Modern Britain

From the aftermath of World War II to the present day, this part reviews the political, economic, and social changes that defined modern Britain. It also introduces key British inventors, cultural figures, and historical milestones of the 20th century.

Early Britain: From Hunters to the Iron Age

The earliest known inhabitants of Britain were Stone Age hunter-gatherers, following animal herds across a land bridge that once connected Britain to mainland Europe. Around 10,000 years ago, rising sea levels created the English Channel, isolating Britain from the continent.

Roughly 6,000 years ago, early farmers arrived, likely from southeastern Europe. They constructed homes, burial sites, and ceremonial landmarks like Stonehenge in Wiltshire, believed to be used for seasonal rituals. Sites such as Skara Brae in Orkney provide insight into Stone Age life and remain some of Europe’s best-preserved prehistoric settlements.

The Bronze Age began around 4,000 years ago, bringing new metalworking skills. People lived in roundhouses, buried their dead in barrows, and created intricate bronze and gold tools, jewelry, and weapons.

The Iron Age followed, with advancements in metal tools and the development of larger, fortified settlements known as hill forts—one notable example is Maiden Castle in Dorset. These people spoke Celtic languages, some of which are still spoken today in Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. They also introduced the first coins in Britain, many of which bore the names of Iron Age kings—marking the beginning of recorded British history.

The Romans in Britain

In 55 BC, Julius Caesar led the first Roman incursion into Britain, but it wasn’t until AD 43 under Emperor Claudius that Rome succeeded in conquering much of the island. Not all regions surrendered easily—Boudicca, queen of the Iceni tribe, famously led a rebellion and is honored with a statue near Westminster Bridge in London.

The Romans never fully subdued Scotland, so Hadrian’s Wall was built in northern England to deter Pictish raids. Remnants of the wall, including Housesteads and Vindolanda forts, are now popular tourist attractions and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Over their 400-year occupation, the Romans built roads, cities, and public buildings, introduced Roman law, and brought new agricultural techniques. The first Christian communities in Britain also appeared during this time.

Anglo-Saxons and the Roots of English

After the Roman legions left in AD 410, tribes from northern Europe—Angles, Saxons, and Jutes—invaded. These groups laid the foundation for the English language. By AD 600, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were established, especially in England. A famous burial site from this period is Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, where a king was laid to rest with treasures inside a ship grave.

Although initially pagan, the Anglo-Saxons were gradually converted to Christianity by missionaries from Ireland and Rome, including St Patrick, St Columba, and St Augustine, who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury.

The Viking Invasions and Integration

Beginning in AD 789, Vikings from Denmark and Norway raided and later settled in Britain. They established communities, particularly in the Danelaw area of eastern and northern England, leaving their mark in place names like Grimsby and Scunthorpe. Over time, many Vikings adopted Christianity and integrated into local societies.

While Anglo-Saxon kings continued to rule most of England, Danish kings like Cnut (Canute) also held power briefly. In Scotland, Viking pressure prompted the unification of tribes under Kenneth MacAlpin, and the term Scotland began to take hold.

The Norman Conquest

In 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, invaded and defeated King Harold at the Battle of Hastings, claiming the English throne. Known as William the Conqueror, his victory marked the beginning of Norman rule. The story of this conquest is famously depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, still preserved in France.

The Norman Conquest and Its Lasting Impact

The Norman Conquest in 1066 marked the last successful invasion of England by a foreign power, bringing about profound shifts in English society and governance. Led by William the Conqueror, the Normans reshaped the ruling class, introduced feudalism, and influenced the evolution of the English language through Norman French. Though they initially extended their reach into Wales, the Welsh gradually reclaimed much of their land. In contrast, Scotland resisted full conquest, despite Norman efforts along the border.

One of William’s most significant administrative achievements was the commissioning of the Domesday Book—a detailed survey of England’s landowners, villages, livestock, and resources. This document still exists and remains a vital window into medieval English life just after the Norman arrival.

Understanding Britain’s Early History and the Norman Legacy

To fully grasp the UK’s historical journey, it’s essential to understand:

-

The pre-Roman civilizations of Britain

-

How Roman rule transformed British society

-

The post-Roman invasions and their cultural influence

-

Why the Norman Conquest of 1066 was a pivotal turning point

Life and Conflict in the Middle Ages

Following the Norman Conquest, the medieval period—spanning roughly 1000 years from the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 AD to 1485—was marked by frequent internal and external wars.

English monarchs fought to assert control over Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. In Wales, England eventually established full authority. In 1284, King Edward I passed the Statute of Rhuddlan, officially incorporating Wales into the English Crown. Fortresses such as Caernarfon and Conwy were built to maintain dominance. By the mid-15th century, Welsh resistance had ended, and English language and law became dominant.

Scotland, however, proved more resilient. In 1314, Robert the Bruce famously led the Scots to victory over the English at the Battle of Bannockburn, securing Scottish independence for generations.

Initially an independent kingdom, Ireland saw English troops arrive to assist a local ruler. Over time, the English consolidated control, especially around Dublin in an area known as the Pale, while some Irish lords recognized English authority.

Beyond the British Isles, English knights participated in the Crusades, religious wars aimed at capturing the Holy Land. Meanwhile, the English fought France in the prolonged Hundred Years’ War, a conflict that included the legendary 1415 Battle of Agincourt, where King Henry V led a vastly outnumbered English army to victory. England eventually withdrew from France by the 1450s.

The Black Death and Social Transformation

The medieval economy was structured around feudalism, where land was exchanged for military service. Peasants, particularly serfs, worked on their lord’s land and had limited personal freedom. This system also took root in parts of Scotland and Ireland.

In 1348, the Black Death—likely a form of bubonic plague—swept through Britain, wiping out nearly one-third of the population. With fewer workers available, surviving peasants demanded higher wages and greater mobility. This period saw the rise of new social groups, including wealthy landowners and a growing middle class in urban areas.

In Ireland, the plague significantly affected the Pale, reducing English control temporarily.

Legal and Political Evolution

Medieval Britain witnessed major legal and governmental changes. The origins of the modern UK Parliament began with the king’s advisory council, made up of nobles and church leaders.

A turning point came in 1215 when King John was forced by his barons to sign the Magna Carta. This historic document limited royal authority, asserting that the monarch must also obey the law. It established principles that would shape the future of British democracy, including requiring the king to seek baronial consent for new taxes or legal reforms.

Over time, Parliament evolved into two houses: the House of Lords (nobles and clergy) and the House of Commons (elected knights and wealthy townspeople). Scotland developed a similar system with three Estates—nobles, clergy, and commoners.

The period also marked the rise of a more structured legal system. English judges built ‘common law’ by following past rulings. In Scotland, laws were systematically recorded in written form, establishing a separate legal tradition.

Shaping a National Identity

The Middle Ages saw the blending of Anglo-Saxon and Norman French into a single English language. Over time, English became the dominant language of government and the courts. By 1400, even royal and official documents were written in English.

One major literary milestone was Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, a collection of stories told by pilgrims traveling to Canterbury. These tales were among the first books printed in England, thanks to William Caxton, the country’s first printer. Many of these stories remain popular today.

In Scotland, Gaelic remained widely spoken, and a distinct Scots language developed. Writers like John Barbour contributed to this cultural evolution with works such as The Bruce, chronicling Scotland’s fight for independence.

Architecture flourished as well, with the construction of imposing castles and awe-inspiring cathedrals like Lincoln and York Minster. These buildings featured stained-glass windows that narrated Christian stories and still captivate visitors today.

Trade also expanded during this era. England became a key exporter of wool, drawing skilled artisans from across Europe. Weavers from France, glassmakers from Italy, engineers from Germany, and Dutch canal builders all brought valuable expertise to Britain’s growing towns.

The Wars of the Roses: A Battle for England’s Crown

In 1455, England was plunged into a civil war over the rightful heir to the throne. Two powerful families—the House of Lancaster and the House of York—clashed in a series of brutal battles known as the Wars of the Roses. The name comes from each family’s emblem: a red rose for Lancaster and a white rose for York.

This prolonged conflict came to an end in 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth Field. King Richard III, the Yorkist ruler, was defeated and killed in battle. His rival, Henry Tudor from the Lancastrian side, emerged victorious and was crowned King Henry VII.

To bring unity to the divided nation, Henry VII married Elizabeth of York—King Richard’s niece. This strategic marriage joined the two rival houses and marked the beginning of the Tudor dynasty. As a symbol of peace and unity, the new royal emblem became a red rose with a white rose at its center, combining both family crests into what is now known as the Tudor Rose.

What You Should Know from This Period

-

The major civil wars that shaped medieval England

-

The early rise and role of Parliament

-

How land ownership was structured under feudalism

-

The social and economic aftermath of the Black Death

-

The roots of the English language and its evolving culture

-

How the Wars of the Roses led to the creation of the Tudor dynasty

The Tudors and the Stuarts: Power and Religious Upheaval

With the end of the Wars of the Roses, King Henry VII focused on restoring stability and strengthening royal authority across England. Determined to avoid further civil unrest, he centralized government control and weakened the influence of powerful nobles. Known for his financial prudence, he built up a healthy reserve in the royal treasury.

When Henry VII died, his son Henry VIII inherited the throne and continued to expand royal power. Henry VIII would later become one of England’s most famous—and controversial—monarchs, best known for separating the English Church from Rome and for his six marriages, which shaped the course of English history and religion.

The Wives of Henry VIII and the English Reformation

King Henry VIII is remembered as one of the most iconic rulers of England—not only for his powerful reign but also for his six marriages, which dramatically reshaped the nation’s religious landscape.

-

Catherine of Aragon – A Spanish princess and Henry’s first wife. Though she bore several children, only their daughter Mary survived. When Catherine could no longer bear children, Henry sought to annul the marriage, desperate for a male heir.

-

Anne Boleyn – An English noblewoman, Anne gave birth to a daughter, Elizabeth. Her time as queen was brief and turbulent—accused of adultery, she was executed at the Tower of London.

-

Jane Seymour – Henry’s third wife gave him the long-awaited son, Edward. Tragically, she died shortly after childbirth.

-

Anne of Cleves – A political alliance led Henry to marry the German princess, but he found her unsuitable and quickly annulled the marriage.

-

Catherine Howard – A cousin of Anne Boleyn, Catherine also faced accusations of infidelity and was executed.

-

Catherine Parr – The last of Henry’s wives, she outlived him and remarried after his death, although she died not long after.

To end his first marriage, Henry needed the Pope’s blessing. When the Pope refused, Henry took radical action—he separated from the Roman Catholic Church and formed the Church of England, with himself as its head. This marked the beginning of the English Reformation.

The Reformation and Its Impact on Britain

Across Europe, a powerful religious movement was taking shape. The Protestant Reformation challenged the authority of the Pope and traditional Catholic practices. Reformers believed individuals should read the Bible in their native languages and have a direct connection with God without intermediaries like saints or clergy.

Protestant beliefs began to spread through England, Wales, and Scotland in the 1500s. However, in Ireland, efforts to enforce Protestantism and English land laws sparked resistance and led to widespread conflict with native Irish chieftains.

During Henry VIII’s reign, Wales was formally united with England through the Act of Union, granting Welsh representation in the English Parliament and aligning the Welsh legal system with England’s.

The Monarchs After Henry VIII

After Henry’s death, his son Edward VI, a staunch Protestant, became king. During his short reign, the Book of Common Prayer was introduced—a text still used in Anglican services today. Edward died young, and his half-sister Mary I, a devoted Catholic, took the throne. She sought to restore Catholicism and persecuted Protestants, earning her the nickname “Bloody Mary.” She too died without a long reign.

Mary was succeeded by her half-sister Elizabeth I, daughter of Anne Boleyn. A Protestant, Elizabeth reinstated the Church of England but allowed some religious tolerance. She avoided severe conflict by carefully balancing the expectations of both Catholics and Protestants. Her popularity soared after England’s decisive victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588, which attempted to invade and restore Catholic rule.

Scotland’s Reformation and Mary, Queen of Scots

Scotland also embraced Protestant ideas. In 1560, the Scottish Parliament declared the Pope’s authority void and outlawed Catholic practices. A new Protestant Church of Scotland emerged, governed by elected leaders rather than the monarchy—unlike the Church of England.

Meanwhile, Mary, Queen of Scots—a Catholic monarch—faced opposition at home. Crowned as an infant, she spent much of her early life in France. Upon returning to Scotland, her reign was marred by scandal and suspicion. When her husband was murdered, Mary was implicated and fled to England, leaving her throne to her Protestant son, James VI. Although she sought Elizabeth I’s help, she was seen as a threat to the English crown and was imprisoned for two decades before being executed for plotting against the queen.

The Golden Age of Exploration and Culture

Elizabeth’s era was one of national pride, overseas expansion, and cultural brilliance. English explorers like Sir Francis Drake sought new trade opportunities and disrupted Spanish interests in the Americas. Drake famously circumnavigated the globe aboard the Golden Hind and played a key role in defeating the Spanish Armada.

During this time, English settlers began to establish colonies along the east coast of North America. Many were motivated by religious differences with the monarchy, laying the groundwork for greater colonization in the next century.

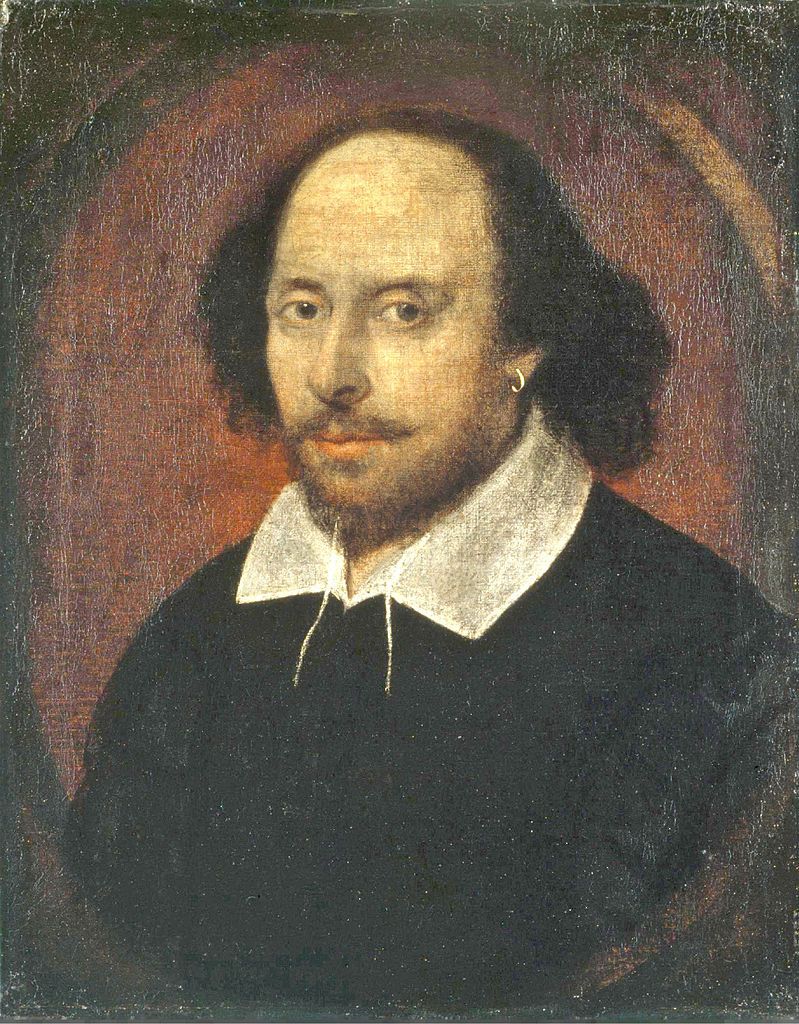

William Shakespeare and the Birth of English Literature

The Elizabethan period is forever linked to William Shakespeare, one of the greatest playwrights in history. Born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, Shakespeare wrote timeless works that continue to influence language, theatre, and literature worldwide.

His famous plays include:

-

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

-

Hamlet

-

Macbeth

-

Romeo and Juliet

Shakespeare also brought everyday people to the stage, not just royalty, and coined many phrases still in use today, such as:

-

“Once more unto the breach” (Henry V)

-

“To be or not to be” (Hamlet)

-

“A rose by any other name” (Romeo and Juliet)

-

“All the world’s a stage” (As You Like It)

-

“The darling buds of May” (Sonnet 18)

Why Shakespeare Is Still Celebrated Today

William Shakespeare is widely regarded as one of the greatest playwrights in history. His timeless plays and poems continue to be performed and studied around the world, including in Britain. The Globe Theatre in London is a modern reconstruction of the original venues where his works first captivated audiences.

James VI and I: The First Stuart King of England

Elizabeth I never married and left no direct heirs. When she passed away in 1603, her successor was James VI of Scotland, who then became King James I of England, Wales, and Ireland. Despite this, Scotland remained a separate kingdom.

The King James Bible: A Lasting Legacy

One of King James I’s notable achievements was commissioning a new English translation of the Bible, now famously known as the King James Version or Authorized Version. Although it wasn’t the first English Bible, this edition remains widely used in Protestant churches today.

Ireland Under English Rule

During this era, Ireland was predominantly Catholic. English monarchs Henry VII and Henry VIII extended their control beyond the Pale, establishing dominance over the entire country. Henry VIII even took the title “King of Ireland.” English laws were imposed, and Irish leaders had to obey directives from the Lord Lieutenants in Dublin.

During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I, many Irish opposed Protestant English governance. Rebellions erupted, prompting the English government to encourage Protestant settlers from Scotland and England to colonize Ulster, a northern Irish province. These settlements, called plantations, displaced many Catholic landowners. James I expanded these plantations throughout Ireland, a policy that had significant long-term effects on the relations between England, Scotland, and Ireland.

The Growing Power of Parliament

Elizabeth I skillfully balanced her authority with that of Parliament, managing to align her goals with those of both the House of Lords and the increasingly Protestant House of Commons.

Her successors, James I and his son Charles I, were less adept politically. Firm believers in the Divine Right of Kings—the belief that monarchs are appointed by God—they resisted parliamentary control. Charles I tried to govern without Parliament when disagreements over religious and foreign policies arose. For 11 years, he raised funds without Parliament’s consent but was forced to recall it due to conflicts in Scotland.

The English Civil War Begins

Charles I’s attempt to impose a more ceremonial Prayer Book on the Scottish Presbyterian Church sparked unrest and rebellion. Scotland formed an army, and Charles needed funds to respond but Parliament refused to provide money, especially as many members were Puritans who opposed the king’s religious reforms.

Ireland also erupted in rebellion, where Catholics feared Puritan influence. Parliament sought control over the English army, a move that threatened royal authority. In response, Charles I famously entered the House of Commons to arrest five parliamentary leaders—an unprecedented act that further escalated tensions.

By 1642, England was divided between supporters of the king, known as Cavaliers, and supporters of Parliament, called Roundheads, marking the start of the English Civil War.

Oliver Cromwell and the Commonwealth

The king’s forces suffered defeats at the Battles of Marston Moor and Naseby. By 1646, Parliament had gained the upper hand and Charles I was captured. Still unwilling to compromise, Charles was executed in 1649.

England then became a republic, known as the Commonwealth, without a monarch. The army held power, with Oliver Cromwell rising as a key leader. He was sent to Ireland to suppress ongoing rebellions, using extreme force that remains controversial today.

Charles I’s son, Charles II, was declared king by the Scots but was defeated by Cromwell at Dunbar and Worcester. Charles II fled to Europe, and England, Scotland, and Wales were governed by Parliament and Cromwell, who became Lord Protector until his death in 1658.

His son Richard succeeded him but lacked authority, leading to political instability. After 11 years as a republic, many sought the return of the monarchy.

The Restoration of the Monarchy

In 1660, Parliament invited Charles II back from exile in the Netherlands. He was crowned King of England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, signaling the monarchy’s return. Charles II agreed to cooperate with Parliament, which generally supported his policies. The Church of England was restored as the state religion, excluding Catholics and Puritans from power.

Turmoil and Renewal in London

During Charles II’s reign, London suffered a devastating plague outbreak in 1665, killing thousands, mostly in poor neighborhoods. The following year, the Great Fire of London destroyed much of the city, including St Paul’s Cathedral. The city was rebuilt with a new cathedral designed by Sir Christopher Wren. Samuel Pepys documented these events in a diary that remains a valuable historical record.

Key Legal and Scientific Advances

The Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 became a cornerstone of legal rights, ensuring no one could be imprisoned unlawfully without a court hearing.

Charles II’s interest in science helped establish the Royal Society, the world’s oldest scientific institution. Notable members included Sir Edmund Halley, famous for predicting the return of Halley’s Comet, and Sir Isaac Newton.

Isaac Newton: A Giant of Science

Born in Lincolnshire, England, Isaac Newton studied at Cambridge University and revolutionized science. His seminal work, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, explained universal gravity. Newton also discovered that white light contains all the colors of the rainbow. His discoveries laid the foundation for modern physics.

The Catholic King James II

Charles II died in 1685 without legitimate heirs. His brother James II, a Catholic, became king. James favored Catholics, appointing them to military posts despite parliamentary bans. He resisted compromise with Parliament and even arrested Anglican bishops, sparking fears he intended to restore Catholic dominance in England.

James’s two daughters were Protestant, reassuring many that the throne would soon return to Protestant rule—until his wife gave birth to a son, raising the possibility of a Catholic dynasty.

The Glorious Revolution: A Turning Point in British History

James II’s eldest daughter, Mary, was married to her cousin William of Orange, the Protestant ruler of the Netherlands. In 1688, key Protestant leaders in England invited William to invade and claim the English throne. When William arrived, he faced no opposition. James II fled to France, allowing William to become King William III of England, Wales, and Ireland—and William II of Scotland. He ruled jointly with Mary. This peaceful change of power is known as the Glorious Revolution because it involved little bloodshed and firmly established Parliamentary authority, preventing future monarchs from ruling without Parliament’s consent.

James II attempted to regain his throne by invading Ireland with French support. However, William defeated him decisively at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, a victory still commemorated in Northern Ireland today. After reclaiming control of Ireland, William forced strict limitations on the Roman Catholic Church and barred Irish Catholics from government participation.

Jacobite Resistance in Scotland

James II had supporters in Scotland as well. A rebellion backing James was crushed at the Battle of Killiecrankie. All Scottish clans were required to swear allegiance to William. The MacDonalds of Glencoe delayed their oath and were subsequently massacred, an event that left lasting resentment and distrust toward the new government.

Many Scots continued to see James as the legitimate monarch. Some joined him in exile in France, while others secretly supported him. These supporters became known as Jacobites.

Key Concepts to Remember:

-

How religion transformed during this era

-

The role of poetry and drama in the Elizabethan age

-

Britain’s involvement in Ireland

-

The evolution of Parliament and England’s brief period as a republic

-

The reasons behind the monarchy’s restoration

-

The causes and effects of the Glorious Revolution

The Rise of Constitutional Monarchy and Parliamentary Power

At the coronation of William and Mary, a Declaration of Rights was read, marking a new era in British governance. This document ensured that monarchs could no longer impose taxes or dispense justice without Parliament’s consent, permanently shifting power away from the crown.

The Bill of Rights (1689) solidified Parliament’s authority, established that future monarchs must be Protestant, and mandated elections for Parliament at least every three years (now five years). Monarchs were also required to seek Parliament’s approval annually to fund the army and navy.

The Birth of Party Politics and a Free Press

These political shifts made it necessary for monarchs to work with ministers who could command parliamentary support. Two main political factions emerged: the Whigs and the Tories (the latter is the predecessor of today’s Conservative Party). This period marked the beginning of party politics in Britain.

Freedom of the press also advanced. Starting in 1695, newspapers could be published without government licensing, leading to a rise in independent journalism.

Constitutional Monarchy Takes Shape

The post-Revolution laws laid the foundation for constitutional monarchy. While the monarch remained influential, Parliament’s power grew, especially through its control over finances and legislation. However, this system was not a full democracy: only property-owning men could vote, women were excluded, and some electoral districts were controlled by wealthy patrons, known as pocket boroughs or rotten boroughs due to their tiny or manipulated electorates.

Population Growth and Immigration

This era saw significant migration. Many people left Britain and Ireland to settle in American colonies, while others arrived in Britain. Notably, the first Jewish families since the Middle Ages settled in London in 1656. Between 1680 and 1720, numerous Huguenot refugees from France, fleeing religious persecution, arrived. Skilled and educated, they contributed to science, banking, textiles, and other industries.

The Act of Union and the Formation of Great Britain

With Queen Anne’s death and no surviving heirs, the succession became uncertain. To unify the kingdoms, the Act of Union (called the Treaty of Union in Scotland) was passed in 1707, creating the Kingdom of Great Britain. Scotland ceased to be independent but retained its own legal system, educational institutions, and Presbyterian Church.

The First Prime Minister and the Hanoverian Succession

After Queen Anne died in 1714, Parliament selected George I, a German Protestant and Anne’s closest Protestant relative, as king. Scottish Jacobites tried—and failed—to replace him with James II’s son.

George I’s limited English skills increased his reliance on ministers. The most powerful minister came to be known as the Prime Minister, with Sir Robert Walpole recognized as the first, serving from 1721 to 1742.

The Jacobite Uprising of 1745 and Its Aftermath

In 1745, Charles Edward Stuart—known as Bonnie Prince Charlie and grandson of James II—landed in Scotland to reclaim the throne. He rallied Highland clans and initially succeeded but was ultimately defeated by George II’s forces at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. Charles escaped to Europe.

Following this defeat, the clans’ power diminished drastically. Clan chiefs became landlords loyal to the English crown, while clan members became tenant farmers, paying rent for their lands.

The Highland Clearances and Scottish Emigration

The Highland Clearances began as many landlords cleared small farms (crofts) to raise sheep and cattle, causing widespread evictions in the 19th century. Many displaced Scots emigrated to North America during this period.

Robert Burns: Scotland’s National Bard

Robert Burns (1759–1796), known as The Bard, was a celebrated Scottish poet who wrote in Scots, English, and Scots-English. He also adapted traditional folk songs. His most famous work, Auld Lang Syne, is still sung worldwide to celebrate New Year’s Eve (Hogmanay in Scotland).

The Enlightenment: A Century of Ideas

The 18th century brought the Enlightenment, a surge of new thinking in politics, philosophy, and science. Many key figures were Scottish, including economist Adam Smith and philosopher David Hume. Innovations like James Watt’s steam engine fueled the Industrial Revolution.

A core Enlightenment principle was the right of individuals to their own political and religious beliefs without state interference—a value still upheld in the UK today.

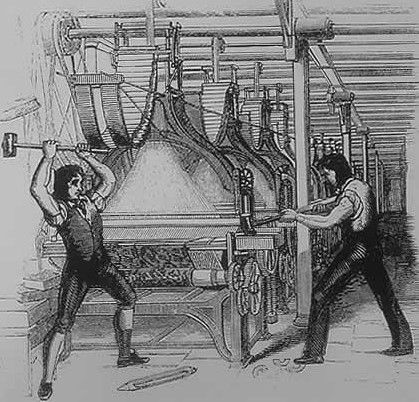

The Industrial Revolution: Britain’s Transformation

Before industrialization, most employment was in agriculture or home-based crafts. The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries transformed Britain with machinery and steam power. Farming and manufacturing became mechanized, dramatically boosting productivity.

The demand for coal and raw materials soared, prompting a population shift from rural areas to cities where mining and factory work thrived.

The Bessemer Process and Its Impact on Industry

The invention of the Bessemer process revolutionized steel production, making it possible to manufacture steel on a large scale. This breakthrough played a crucial role in advancing the shipbuilding industry and expanding the railway network. As a result, manufacturing became the dominant source of employment across Britain.

Richard Arkwright (1732–1792)

Born in 1732, Richard Arkwright initially trained as a barber, specializing in hair dyeing and wig making. When wigs fell out of fashion, he shifted his focus to the textile industry. Arkwright enhanced the early carding machine, which prepares fibers for spinning into yarn and fabric. He also pioneered horse-powered spinning mills operating a single machine, boosting production efficiency. Later, he incorporated steam engines to power his machinery. Arkwright is remembered for managing his factories in an exceptionally efficient and profitable manner.

Improved Transportation Networks

Efficient transportation was essential for moving raw materials and finished products. Canals were constructed to connect factories with towns, cities, and ports, especially in England’s industrial heartlands in the Midlands and the North.

Harsh Working Conditions

During the Industrial Revolution, workers faced extremely poor conditions. Without protective labor laws, employees endured long hours and hazardous environments. Children also worked under the same harsh conditions, often suffering even more severe treatment.

British Colonial Expansion

This era also saw a rise in British overseas colonization. Captain James Cook charted Australia’s coastline, and several colonies were established there. Britain expanded its control over Canada, while the East India Company, originally a trading firm, took control over vast parts of India. Colonies also began to form in southern Africa.

Global Trade and Rivalries

Britain traded globally, importing goods like sugar and tobacco from North America and the West Indies, and textiles, tea, and spices from India and the Indonesian archipelago. Overseas trade and colonization sometimes led to conflicts with other powers, especially France, which competed with Britain in many regions.

Sake Dean Mahomet (1759–1851)

Born in Bengal, India, Mahomet served in the Bengal army before arriving in Britain in 1782. After marrying an Irish woman named Jane Daly in 1786, he eventually settled in London and opened the Hindoostane Coffee House in 1810—the first curry house in Britain. Mahomet and his wife also introduced the Indian practice of shampooing, a form of head massage, to the British public.

The Slave Trade

The commercial growth of Britain was partly sustained by the transatlantic slave trade. Although slavery was banned in Britain itself, by the 18th century it had become a major industry overseas, controlled primarily by Britain and its American colonies. Enslaved people were mostly taken from West Africa under brutal conditions and forced to work on plantations in America and the Caribbean. Many resisted through escape attempts or revolts.

Opposition to slavery grew in Britain during this period. Quaker groups petitioned Parliament to end the trade, and figures like William Wilberforce, a Member of Parliament and evangelical Christian, were instrumental in turning public opinion against slavery. The slave trade was outlawed in British ships and ports in 1807, and slavery itself was abolished throughout the British Empire in 1833. After abolition, millions of Indian and Chinese laborers replaced freed slaves, working in plantations, mines, railways, and military roles across the empire.

The American War of Independence

By the 1760s, British colonies in North America were prosperous and largely self-governing. Many colonists had originally migrated for religious freedom and valued liberty highly. When Britain imposed taxes without granting colonial representation in Parliament, tensions grew. The slogan “no taxation without representation” embodied the colonists’ protest. Despite some compromises, conflict erupted, leading 13 colonies to declare independence in 1776. After years of war, Britain recognized American independence in 1783.

Wars with France

Throughout the 18th century, Britain engaged in multiple conflicts with France. The French Revolution of 1789 escalated tensions, leading to war. Under Napoleon’s rule, France clashed with Britain and its allies. The British Royal Navy famously defeated combined French and Spanish fleets at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, where Admiral Nelson was killed. Nelson’s legacy is commemorated in London’s Trafalgar Square and his ship, HMS Victory, is preserved in Portsmouth. Napoleon was eventually defeated at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 by the Duke of Wellington, known as the Iron Duke.

The Union Flag

Although Ireland shared a monarch with England and Wales since the reign of Henry VIII, it remained a separate kingdom until 1801. The Act of Union united Ireland with England, Scotland, and Wales, forming the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. A new flag, the Union Flag (often called the Union Jack), was created, combining the crosses of St George (England), St Andrew (Scotland), and St Patrick (Ireland). Wales is represented by its own dragon flag but is not included on the Union Flag.

The Victorian Era

Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837 at age 18 and reigned until 1901. Her era was marked by Britain’s expansion in global power and influence. The rising middle class gained importance, and social reform movements worked to improve living conditions for the poor.

The British Empire’s Expansion

During Victoria’s reign, the British Empire grew to include all of India, Australia, and large parts of Africa, becoming the largest empire in history with over 400 million people. Migration increased in both directions: millions of British citizens emigrated overseas, while many immigrants from Russia, Poland, India, and Africa settled in Britain.

Trade and Industry Advances

Britain strengthened its position as a global trading nation by embracing free trade policies and removing tariffs like the Corn Laws of 1846. These changes lowered the cost of raw materials, boosting industry. Factory conditions gradually improved, and laws limited working hours for women and children. The expansion of the railway network and infrastructure projects by engineers like Isambard Kingdom Brunel transformed transport within Britain and across the empire.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859)

Brunel was a pioneering British engineer from Portsmouth who designed tunnels, bridges, railways, and ships. His Great Western Railway connected London to the southwest and Wales. Brunel’s iconic Clifton Suspension Bridge over the Avon Gorge still stands today.

Global Influence and Innovation

In the 19th century, Britain led the world in producing iron, coal, and cotton textiles. London became a financial hub with growing insurance and banking industries. The 1851 Great Exhibition in London’s Crystal Palace showcased British industry and attracted global participation.

The Crimean War (1853–1856)

Britain allied with Turkey and France against Russia in the Crimean War. It was the first war extensively covered by newspapers and photography. Poor conditions caused many deaths from disease rather than battle wounds. Queen Victoria introduced the Victoria Cross to honor soldier bravery.

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910)

Born to English parents in Italy, Nightingale trained as a nurse and gained fame for improving care in Crimean War hospitals. She established the first nursing school in London, revolutionizing healthcare and earning recognition as the founder of modern nursing.

Ireland in the 19th Century

Life in Ireland lagged behind the rest of the UK, with many relying on small-scale farming and potatoes for sustenance. The potato famine of the mid-1800s caused mass starvation and emigration. Irish communities grew in British cities, while nationalist movements pushed for independence or self-governance.

Expansion of Voting Rights

The growing middle class demanded political power, leading to the Reform Acts, which expanded the vote and redistributed parliamentary seats toward industrial towns. However, many working-class men and all women remained disenfranchised. The Chartist movement campaigned for broader voting rights. By the late 19th century, political parties developed strategies to engage voters. Women, meanwhile, fought for suffrage, culminating in partial voting rights in 1918 and equal suffrage in 1928.

Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928)

Pankhurst was a leading figure in the women’s suffrage movement. She co-founded the Women’s Social and Political Union, whose members, known as suffragettes, used militant tactics to demand voting rights. Their efforts helped secure voting rights for women over 30 in 1918 and equal voting rights by 1928.

The Future of the British Empire

Although the empire continued to expand into the early 20th century, debates arose about its sustainability. Conflicts like the Boer War (1899–1902) highlighted challenges. Over time, many colonies gained autonomy and transitioned into the Commonwealth, marking the gradual end of the empire.

Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936)

Born in India, Kipling was a celebrated author and poet who depicted the British Empire positively. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1907. His famous works include The Jungle Book and the poem If, widely admired in the UK.

The 20th Century

World War I

At the dawn of the 20th century, Britain was filled with hope and confidence. With its vast empire, a powerful navy, flourishing industries, and strong political systems, Britain was recognized as a global superpower. This period also saw notable social reforms: financial support for the unemployed, pensions for the elderly, and free school meals were introduced. Laws improved workplace safety, urban planning cracked down on slum growth, and more help was provided to mothers and children after separation or divorce. Local governments grew more democratic, and for the first time, members of Parliament received salaries, encouraging broader participation in politics.

However, this era of progress was abruptly halted by the outbreak of war in Europe. On June 28, 1914, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria sparked a chain reaction that led to the First World War (1914–1918). Although this assassination was the immediate cause, deeper issues like rising nationalism, militarization, imperial ambitions, and divided alliances among European powers set the stage for the conflict.

While the fighting centered in Europe, the war was truly global. Britain was part of the Allies, alongside France, Russia, Japan, Belgium, Serbia, and later Greece, Italy, Romania, and the United States. The entire British Empire was involved, with over a million Indian soldiers fighting in various theaters and suffering approximately 40,000 deaths. Troops also came from the West Indies, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. They battled the Central Powers, mainly Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria. Millions died or were wounded; British casualties alone exceeded two million. One of the deadliest battles was the 1916 Somme offensive, which resulted in around 60,000 British casualties on the first day. The war concluded with an Allied victory at 11 a.m. on November 11, 1918.

The Division of Ireland

In 1913, the British government proposed ‘Home Rule’ for Ireland, which would allow Ireland to govern itself through its own parliament while remaining part of the UK. This plan faced strong opposition from Protestant communities in Northern Ireland, who vowed to resist it by force.

The First World War delayed any political changes in Ireland, but nationalist groups refused to wait. In 1916, the Easter Rising—an armed rebellion in Dublin—challenged British rule. Its leaders were executed, leading to a guerrilla campaign against British forces. A peace agreement was reached in 1921, and by 1922 Ireland was divided. The mainly Protestant six northern counties stayed within the UK as Northern Ireland, while the rest became the Irish Free State, later declared a republic in 1949.

Disagreements over this partition persisted, with some in both regions wanting a united, independent Ireland. These tensions eventually escalated into a violent conflict known as ‘the Troubles,’ centered around the struggle between Irish nationalists and those loyal to Britain.

The Interwar Years

The 1920s brought improved living conditions for many. Public housing projects expanded and new homes were built in towns and cities. However, the 1929 onset of the Great Depression triggered widespread unemployment in parts of the UK. The impact varied: traditional heavy industries like shipbuilding declined, while newer sectors such as automotive and aviation grew. Falling prices meant workers often had more disposable income. Car ownership doubled from one to two million by 1939, and housebuilding continued. This era also saw cultural growth with writers like Graham Greene and Evelyn Waugh, economic ideas from John Maynard Keynes, and technological milestones—BBC radio began in 1922 and the first regular TV service launched in 1936.

World War II

Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany in 1933, blaming the post-World War I treaties for his country’s hardships and seeking territorial expansion. He rebuilt Germany’s military strength and defied international agreements. Britain initially aimed to avoid conflict, but when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, Britain and France declared war to stop further aggression.

World War II pitted the Axis powers—Germany, Italy, and Japan—against the Allies, which included the UK, France, Poland, Austria, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa. Hitler’s forces quickly took Austria and Czechoslovakia, then invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, and France by 1940. Amid this crisis, Winston Churchill became Prime Minister and led Britain through its darkest hours.

Winston Churchill (1874–1965)

Churchill, son of a politician, had been a soldier, journalist, and Conservative MP since 1900. Appointed Prime Minister in May 1940, he inspired the British people with his determination never to surrender to Nazi Germany. Though he lost the 1945 election, he returned as Prime Minister in 1951 and served until 1964. Upon his death in 1965, he was honored with a state funeral and remains one of Britain’s most respected leaders. In 2002, he was voted the greatest Briton ever.

During the war, Churchill’s speeches rallied the nation, with famous lines such as:

-

“I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.” (First speech as Prime Minister, 1940)

-

“We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.” (After Dunkirk, 1940)

-

“Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” (During the Battle of Britain, 1940)

The Evacuation at Dunkirk and the Resilience of Britain During WWII

As France was overtaken during World War II, the British launched a massive naval evacuation to rescue British and French troops trapped on French soil. Remarkably, numerous civilian volunteers used small fishing and pleasure boats to assist the Royal Navy in rescuing over 300,000 soldiers from the beaches surrounding Dunkirk. Despite significant losses in men and equipment, the operation was deemed a success, enabling Britain to continue its resistance against Nazi Germany. This event inspired the famous phrase, “the Dunkirk spirit.”

From June 1940 until Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Britain and its Empire stood nearly alone against the might of Nazi Germany.

The Battle of Britain and the Blitz

Adolf Hitler aimed to invade Britain but first needed to secure air superiority. The Royal Air Force (RAF), equipped mainly with British-designed Spitfires and Hurricanes, fiercely defended British skies during the summer of 1940. This pivotal conflict, known as “the Battle of Britain,” ended with a critical RAF victory. However, German forces continued nightly bombings known as the Blitz, devastating cities such as Coventry and parts of London’s East End. Despite the destruction, a strong national resolve endured, known today as “the Blitz spirit,” symbolizing unity in adversity.

Global Conflict and Turning Points

While defending the homeland, British forces fought Axis powers across the globe. Japan’s advances included the fall of Singapore and occupation of Burma, threatening India’s safety. The United States joined the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. That same year, Hitler launched a massive invasion of the Soviet Union, resulting in intense battles and heavy casualties on both sides. Ultimately, Soviet forces pushed back the Germans, marking a crucial turning point in the war.

The Allies gradually gained momentum, securing key victories in North Africa and Italy. With American support and German losses in the Soviet Union, the Allies launched the historic D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, landing in Normandy. This led to the liberation of France and the eventual defeat of Germany in May 1945.

The End of the War and the Atomic Age

The conflict with Japan concluded in August 1945 after the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. British scientists, including those led by Ernest Rutherford, contributed foundational work in nuclear physics that played a role in the development of atomic weapons. The war’s end ushered in a new era of science and geopolitics.

Alexander Fleming and the Discovery of Penicillin

Scottish-born Alexander Fleming revolutionized medicine in 1928 by discovering penicillin while researching the flu virus. Later developed into a practical antibiotic by Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, penicillin became widely produced by the 1940s and remains a cornerstone in fighting bacterial infections. Fleming received the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1945.

Post-War Britain: Welfare and Reconstruction

After World War II, Britain faced economic exhaustion and a strong public desire for social reform. The 1945 election brought the Labour Party to power under Clement Attlee, who implemented the welfare state envisioned in the Beveridge Report. The National Health Service (NHS), launched in 1948 under Minister Aneurin Bevan, provided free healthcare at the point of use for all citizens. Social security benefits and the nationalisation of industries like railways, coal, gas, and electricity were key aspects of this transformation.

Simultaneously, many British colonies began gaining independence, including India, Pakistan, and Ceylon in 1947, with others following in the ensuing decades.

Cold War and Economic Growth

Britain developed its own atomic bomb and joined NATO to counter the Soviet threat. The Conservative government from 1951 to 1964 oversaw economic recovery and growing prosperity. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan famously spoke of a “wind of change,” referring to decolonisation and the independence of former colonies.

Social and Cultural Shifts in the 1960s

The 1960s, known as the Swinging Sixties, saw rapid social changes, including new fashions, cinema, and music from icons like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. Legal reforms advanced women’s rights, including equal pay laws and anti-discrimination measures. Britain also made technological strides, exemplified by the development of the supersonic Concorde aircraft.

Immigration from the West Indies, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh played a crucial role in addressing labor shortages but was later limited by new laws requiring close British ties.

Notable British Inventions of the 20th Century

Britain has been home to many groundbreaking inventions, including:

-

The television, pioneered by John Logie Baird

-

Radar technology developed by Sir Robert Watson-Watt

-

The radio telescope at Jodrell Bank by Sir Bernard Lovell

-

The foundational work in computing by Alan Turing

-

Discovery of insulin by John Macleod

-

DNA’s structure uncovered at British universities, including work by Francis Crick

-

The jet engine by Sir Frank Whittle

-

The hovercraft by Sir Christopher Cockerell

-

The supersonic Concorde plane (in partnership with France)

-

The vertical take-off Harrier jet

-

The first ATM by James Goodfellow

-

IVF technology developed by Sir Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe

-

The cloning of Dolly the sheep led by Sir Ian Wilmot and Keith Campbell

-

The MRI scanner co-invented by Sir Peter Mansfield

-

The World Wide Web, invented by Sir Tim Berners-Lee

Economic Challenges and Political Changes in the 1970s

The post-war economic boom ended during the 1970s, causing inflation, unstable currency, and labor strikes. The period also saw conflict in Northern Ireland, leading to direct rule from London and significant loss of life.

Britain’s Evolving Role in Europe and the World

The UK was a founding member of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957, later the European Union, but opted out of the Euro currency. The UK formally exited the EU on January 31, 2020.

Conservative Rule and Modern Politics

Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government (1979–1990) implemented economic reforms, privatised industries, and curbed trade union power. The Falklands War in 1982 reaffirmed British sovereignty over the islands. Her successor, John Major, advanced the Northern Ireland peace process.

Labour Government and 21st Century Conflicts

Tony Blair’s Labour government (1997–2010) established devolved parliaments for Scotland and Wales and advanced the Northern Ireland peace process. Britain participated in global military actions in the Gulf War, Balkans, Afghanistan, and Iraq, focusing on counter-terrorism and security.

Recent Developments and Brexit

The 2010 coalition government under David Cameron led to a 2016 referendum, where Britain voted to leave the EU. Cameron resigned, succeeded by Theresa May and then Boris Johnson. The UK officially left the European Union in 2020.